Warm Winter Weather Stimulates Insect Emergence and Growth

go.ncsu.edu/readext?915263

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲A quick alert email came in last night from the Eastern Nursery Specialist at NC State University warning us about the potential early emergence of the minor Ambrosia beetle, a pest for gardens, nurseries and forestry projects alike. These insects can hone in on weakened trees, bore into their bark, feed on the wood, and inoculate the tree with fungus that rots the wood from the inside out. Some of our favorite spring-flowering trees and pines are their favorites. Yikes!

Spring-like weather in the 70s is on the horizon for Eastern North Carolina this weekend, and nursery people, foresters and farmers need to be on alert for the next week as these warm temperatures will be a signal to insects to become active. While the spring peeper frogs and the daffodils are starting up, we still have more than a month left in ‘winter’ and more weeks still until the first frost free date

Crocus – photo by Amanda Wilkins

(estimated to be about April 1-14 here). These mixed signals not only confuse us humans, but they can also trigger responses in plants and animals. Of concern are insects that are crop pests, like the minor ambrosia beetle.

Insects are ectothermic

One of the great fascinations of nature is that insects are ectothermic, meaning they are cold blooded and their internal temperature tracks with the ambient temperature around them. This phenomenon has been observed for hundreds of years but was first published in the 1930s. Most insect species undergo a process called ‘chill coma’, which, like it sounds, means they enter into a state of low movement and metabolism as the temperature drops. This doesn’t protect them from cold or freezing temperatures indefinitely. Different insect species are still killed at different cold temperatures. We rely on this in temperate climates in order to reduce insect populations and kill undesirable tropical insects that can sometimes hitch a ride north during the warmer months.

On the other hand, when the temperatures are warm, there is an increase in insect activity and metabolism, and as the temperature rises and stays warm (around 70 degrees Fahrenheit, it takes less time for insects to complete their life cycles.

Why should we care?

Temperature is the most important factor when it comes to insect activity and metabolism. All other factors, such as food availability, photoperiod, light, population density, pesticides, humidity and insect pathogens, do not have the direct and cumulative effect temperature does on insects.

Farmers, foresters and nursery people already know insects can negatively affect their crop’s health. As our winters get more mild and our ‘springs’ come sooner, this means: more insects will survive; less desirable species may survive to the next season; insects will emerge sooner; and they have longer to mature and create another generation of insects. This means more time, effort and money will need to be spent managing the pest.

Insect pests can damage or destroy the crop and result in crop failure if they are not monitored for or managed in a timely manner. Chemical pest control begins when the insect population reaches the economic threshold in the concept of Integrated Pest Management, meaning that it is no longer cost effective to allow the insect pest to continue to damage the crop and action must be taken. Chemical recommendations are usually made based on the life stage of the pest in question, maturity of the crop being treated, and the weather conditions, in most cases. These chemicals are studied and tested to make sure that when a crop manager is applying them the crop is not going to be negatively affected by the application and desired effect is achieved. If insect pests are emerging out of this understood cycle, then this could potentially result in ineffective pesticide sprays.

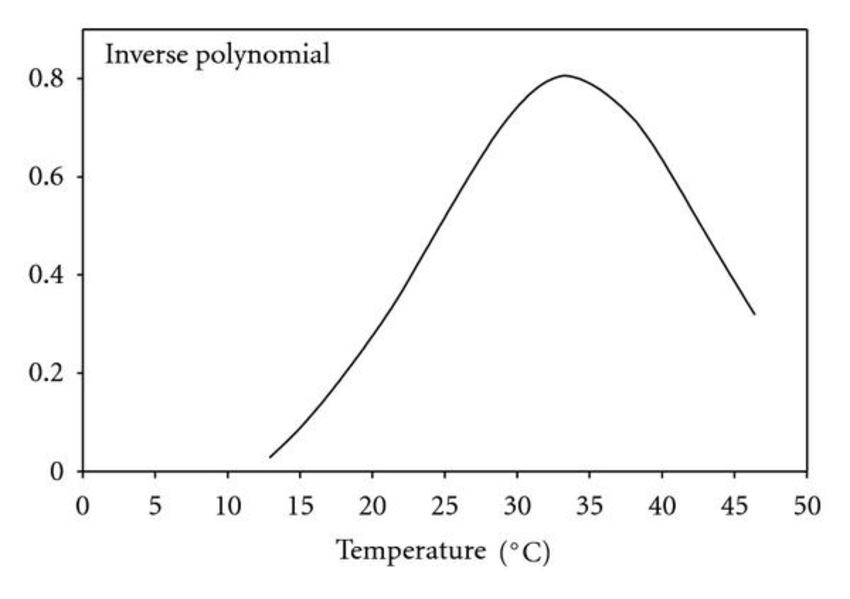

Inverse Curve- This curve shows the relationship between temperature and insect development. Diagram from: Damos, Petros & Savopoulou-Soultani, Matilda. (2012). Temperature-Driven Models for Insect Development and Vital Thermal Requirements. Psyche. 2012. 1-13. 10.1155/2012/123405.

What can we do?

Any gardener or farmer will tell you that the weather rules the day. Paying attention to the forecast and how nature responds to it can help you understand the underlying patterns, and this can help you develop a sense of timing in the landscape. The modern scientific term for this is ‘scouting’, but humans have been doing this for hundreds of thousands of years. Monitoring for insect pests and diseases on your desirable crops is just good, basic horticultural and agricultural practice. Using this data will inform if and when you need to take action. Through scouting, observation and study, and understanding the economic thresholds for insect pests we can adapt to the changing climate conditions.

Insects are critical to the overall function of the ecosystem, and only one percent of insects around the world are actually true pests (Nature, 2011). They can help us understand what is happening around us as they go about their lives. We can still enjoy the warm weather and revel in the emerging spring flowers, but we should remain ever diligent and observant as new patterns emerge each year.

Amanda Wilkins is the Horticulture Agent for North Carolina Cooperative Extension in Lee County.